Inhabitable ? Vous avez dit inhabitable ?

Uninhabitable? Did You Say Uninhabitable?

Un problème proposé par Olivier Lazzarotti

« Car la leçon de ces histoires est simple et à la portée de tous. Politiquement parlant, elle est que, dans des conditions de terreur, la plupart des gens s’inclineront, mais que certains ne s’inclineront pas ; de même, la leçon que nous donnent les pays où l’on a envisagé la Solution finale, est que “cela a pu arriver” dans la plupart d’entre eux, mais que cela n’est pas arrivé partout. Humainement parlant, il n’en faut pas plus, et l’on ne peut raisonnablement pas en demander plus, pour que cette planète reste habitable pour l’humanité. »

Avec cette citation d’Hannah Arendt est posée, tout à la fois et dans leurs dialogues, la question de l’habitable et de l’inhabitable. Défiant toutes les logiques : l’inhabitable habité existerait-il ?

De fait, la définition de l’habiter a fortiori au-delà de se loger et comme dimension spatiale des sociétés est assez bien cernée par les sciences sociales. Sans être tout à fait d’accord entre elles, elles en posent les enjeux. A contrario, celle de l’inhabitable reste l’une des questions les plus ardues, les plus insaisissables, les plus obscures du moment contemporain. Qu’est-ce à dire ?

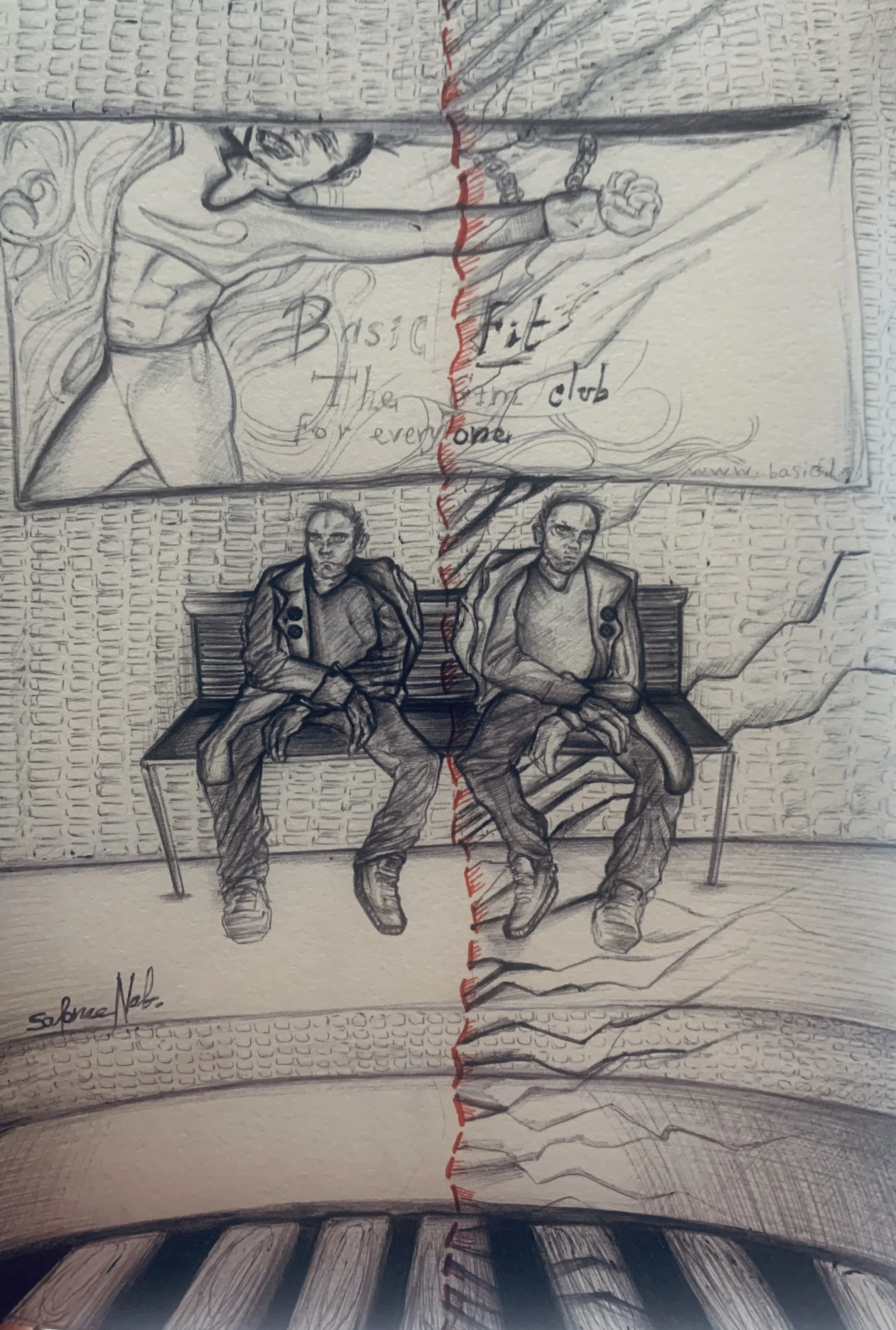

L’inhabitable réside-t-il dans la privation des autres, de tous les autres, autrement dit et plus encore que dans l’exil, dans la solitude absolue ?

Ou bien : si habiter ce n’est pas seulement être dans un lieu, mais produire son lieu, l’inhabitable serait-il de ne pouvoir singulariser son propre lieu et de subir, implacablement, l’absolu totalitarisme de l’enfermement ?

Exploration des bornes de la vie et du vivant, la question se profile autrement quand elle est posée dans ses dimensions politique et existentielle. L’inhabitable des uns n’est peut-être pas l’inhabitable des autres. De même l’inhabitable pour les uns pourrait bien être une production des autres.

Le problème est donc le suivant : qui, et selon quels critères, peut décider de ce qui est inhabitable, et le définir ?

"For the lesson of these stories is simple and within everyone's reach. Politically speaking, it is that under conditions of terror, most people will bow, but some will not; similarly, the lesson from the countries where the Final Solution was envisioned is that "it may have happened" in most of them, but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is needed, and no more can reasonably be asked for, to keep this planet dwelling for humanity.”

With this quote from Hannah Arendt, the question of what is inhabitable and what is uninhabable is raised both in their dialogues and at the same time. Challenge to any logic: the dwelled uninhabitable would therefore exist?

In fact, a beyond-housing definition of inhabiting as the spatial dimension of societies is quite well defined by social sciences. Without totally agreeing with each other, they pose the right challenges.

On the contrary, the definition of the uninhabitable remains one of the most difficult, elusive and obscure questions of the contemporary world. What does this mean?

Does the uninhabitable reside in the deprivation of others, of all others, in other words and even more than in exile, in absolute solitude?

Or: if inhabiting is not only to be in a place, but to produce one's place, would the uninhabitable be to be unable to singularize one's own place and to suffer, implacably, the absolute totalitarianism of lockdown ?

Exploring the limits of life and of the living, the question takes on a different profile when it is posed in its political and existential dimensions. The uninhabitale of some may not be the uninhabitable of others. As well as the uninhabitable of some might be produced, by others.

The problem is therefore the following : who, and according to what criteria, can decide what is uninhabiting, and define it?